Populorum Progressio, pubblicata il 26 marzo 1967. Cinquant’anni dopo, la Via della Seta, il complesso infrastrutturale che collegherà sempre più strettamente Cina, Asia centrale e Europa si profila come la possibile concretizzazione di quell’idea — purché si riesca a contenere gli effetti negativi (corruttivi) che accompagnano i grandi investimenti economici. Su tale questione l’Istituto di ricerca sulla pace internazionale di Stoccolma (Sipri) ha pubblicato alcuni studi, disponibili nel sito https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2017/silk-road-economic-belt?utm_campaign=buffer&utm_content=buffer311c9&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com Ne riportiamo qui una citazione significativa:

The Silk Road Economic Belt: How does it interact with Eurasian security dynamics?

China has long posited that common security can be propelled and buttressed through economic development and cooperation. Infrastructure, in turn, is one of the essential foundations of economic development and cooperation—no economically prosperous state has been able to progress without it. As the Chinese put it ‘要想富, 先修路’ (‘if you want to be rich, first build a road’). Large parts of Asia have a critical lack of basic infrastructure such as roads, rail tracks, bridges, airports and power grids, which current national and multilateral developmental institutions are unable to address. This infrastructure deficit is an estimated $4 trillion (pdf) for the period 2017–20 alone. China intends to reduce this deficit in Asia, and in parts of Europe, through the Silk Road Economic Belt (the ‘Belt’) component of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The Belt has, therefore, quite deservedly been received with enthusiasm among many states of the Eurasian continent since its proposal in 2013. It is an ambitious multi-decade vision to physically, digitally and culturally connect Eurasia, pursue closer Eurasian economic cooperation and mitigate poverty. This grand vision has become a pillar of the President Xi Jinping administration’s foreign policy. Opportunities and challenges Foreign policy is always an extension of domestic interests and the Belt intends to serve a wide range of Chinese interests. These include enhancing China’s economic security by increasing its global economic and financial clout, and mitigating current and possible future security threats emanating from its neighbours by promoting their economic growth and subsequent closer economic ties with China. Simultaneously, the Belt is a useful platform to channel China’s surplus production capacity and surplus capital outwards….

The Belt fits well into China’s own security concepts, which stress common security through economic cooperation. The Belt will certainly expand China’s overseas interests and will require China to take a robust position on regional security affairs, not least to protect its investments. Thus, China’s non-interference stance, which has already been evolving over the past few years, will likely become much more ‘creative’ as a result of the Belt.

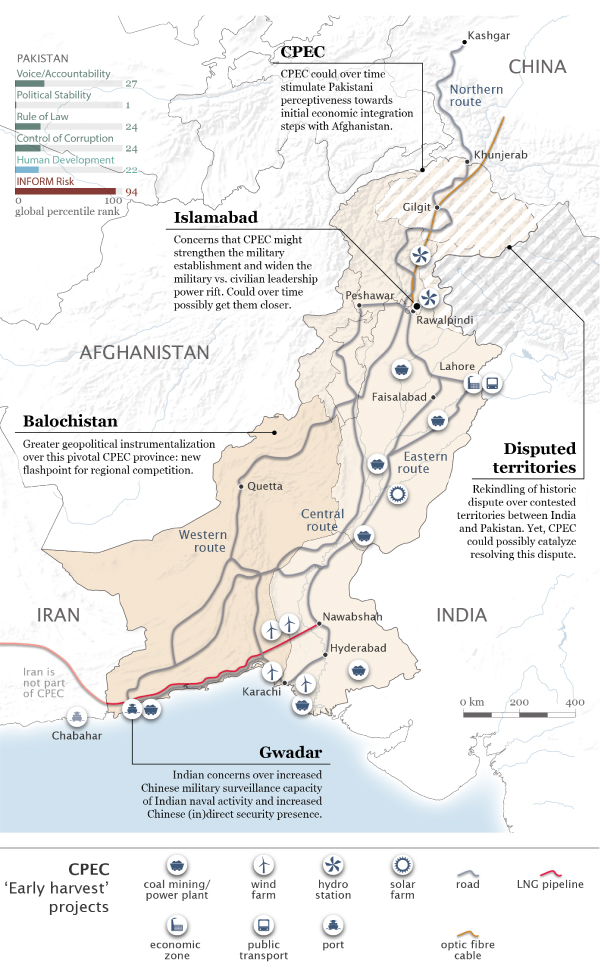

Indeed, China’s evolving stance can already be witnessed in Central and South Asia, where notable examples include the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism to combat terrorism established between the armed forces of China, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Tajikistan in August 2016; the stepping-up by China of military cooperation and security assistance to states participating in the Belt; and the ‘outsourcing’ of military protection of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)—the main Belt corridor in South Asia—to Pakistan.

More broadly, the Belt will interact with Central and South Asian security dynamics in a mutually constitutive way. In Central Asia, it is perceived by the landlocked Central Asian regimes as a means of boosting economic growth, which will have positive spillover effects on security. At the regional level, the financial prospects the Belt offers could also serve to stimulate greater regional cooperation on the range of issues these states face.

However, in South Asia, where the Belt currently only really runs through Pakistan, it has raised regional political temperatures. India has objected to CPEC in the strongest terms (pdf), in part because it traverses territory that is disputed between India and Pakistan. CPEC has exacerbated the pre-existing India–Pakistan rivalry, as well as China–Pakistan competition with India over regional influence and security.

India is concerned about the long-term geopolitical implications of CPEC, particularly that China will gain more regional influence at the expense of India. India fears that investment protection and protection of future transit through Pakistan will increase China’s security role in South Asia, and has concerns about a possible naval base in the port city of Gwadar in Pakistan, one of the BRI’s key strategic investments.

Afghanistan, in contrast to India, welcomes the Belt, but the country’s instability and difficult ties with Pakistan will deter it from becoming an established Belt participating state—at least for the foreseeable future.

|

||

Map of South Asia illustrating China–Pakistan Economic Corridor projects and interaction with South Asian security dynamics. Graphic: Christian Dietrich |